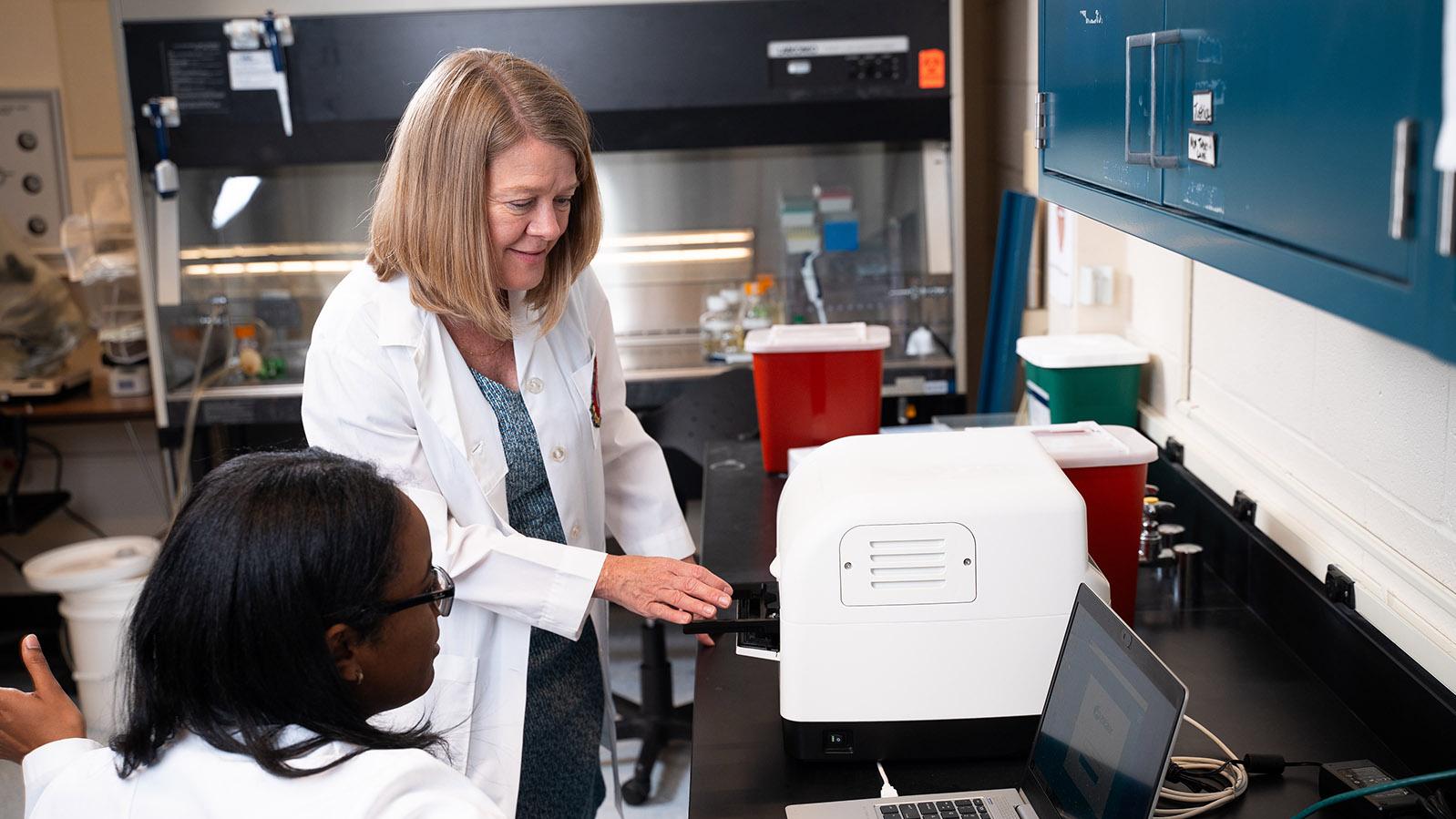

Ohio State nurse scientists Dr. Shannon Gillespie, left, and Dr. Jodi Ford at the Pitzer Center in Jane E. Heminger Hall.

(All photos courtesy of The Ohio State University College of Nursing)

Ohio State nurse scientists Dr. Shannon Gillespie, left, and Dr. Jodi Ford at the Pitzer Center in Jane E. Heminger Hall.

(All photos courtesy of The Ohio State University College of Nursing)

In 2001, Mary Lynn Pitzer got some exciting news: She was pregnant with triplets.

Jitters accompanied the anticipation, of course. The idea of birthing and caring for three infants felt daunting, especially for a first-time mom. But Mary Lynn and her husband, David, also knew they had an invaluable resource—someone who could coach them through every stage, from pregnancy to delivery and all the hectic months to follow. David’s mother was in their corner.

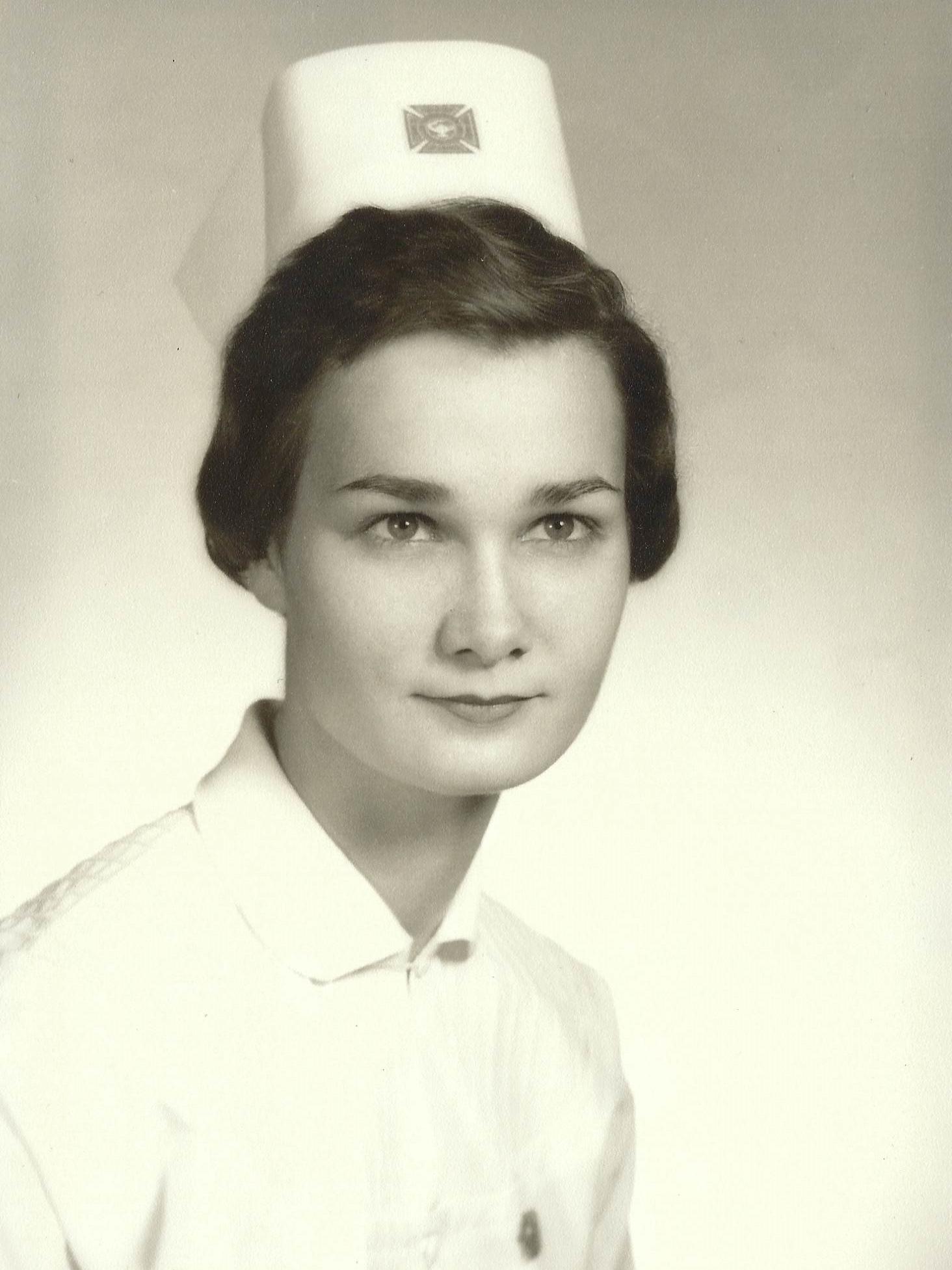

Martha S. Pitzer, PhD, RN (’74 BSN, ’76 MS, ’84 PhD), spent decades answering the call to care as a nurse and educator. A California native, she came to Columbus in 1968 with her three kids—David, Ken and Susan—and husband Russell Pitzer, who took a job with The Ohio State University Department of Chemistry, where he remained for 40 years. As Russ’ career progressed, Martha charted her own academic path, earning three degrees and teaching nursing students at both Otterbein College and Ohio State.

After years of caregiving work with mothers and children, Martha’s wisdom, selfless attitude and steadying presence made her the perfect person to help Mary Lynn, David and the forthcoming triplets. “This was the culmination of everything she was interested in,” Mary Lynn says.

But not everything went as planned. Twenty-four weeks into the pregnancy, Mary Lynn had a sensation that didn’t feel right. She called her doctor, who advised a trip to the emergency room. Soon enough, she was put on bedrest in the hospital in hopes of preventing preterm labor.

“That was a big surprise, and it derailed my plans for being at home until I had the babies. But I knew it was going to be OK. Martha’s presence was so calming. She’d just say, ‘We’ll figure this out,’” Mary Lynn says. “As the weeks went on, she was a huge support, visiting and making sure I was an important patient. Everybody loved and knew Martha.”

After about 10 weeks of bedrest, Mary Lynn gave birth to three healthy babies—Joy, Noah and Elizabeth. Martha continued being an advocate and helper, even sleeping on a cot near the babies. She drew on her work as a lactation consultant and learned all the strategies for breastfeeding triplets, becoming an expert and later helping other moms of multiples.

“If I had a question and she didn't know the answer, she was thrilled to dive in and find out,” Mary Lynn says. “She’d say, ‘This is something we can do together.’”

Martha Pitzer remained a loving presence in the lives of her kids and grandkids until her death in 2016. Before she passed away, the Pitzer Family Foundation created a scholarship in her name, the Dr. Martha S. Pitzer Nursing Endowed Scholarship Fund, which opens academic pathways for students at the College of Nursing. Then, in the early days of Time and Change: The Ohio State Campaign, the Pitzer Family Foundation gave $3 million to create the Martha S. Pitzer Center for Women, Children and Youth at the College of Nursing.

As a center that provides world-class educational opportunities for nursing students while also fostering an environment of research discovery, the college could not have picked a more fitting namesake. Martha embodied the role of a nurse scientist—an intensely curious researcher, knowledgeable professor and beloved caregiver who committed her life to helping others.

Launched in 2018 under the direction of Dr. Karen Patricia Williams, the Martha Pitzer Center moved into its new home inside Jane E. Heminger Hall in 2022. This beautiful, state-of-the-art facility, which also benefited from the Pitzers’ gift, was built with wellness in mind and allows for even more collaboration among the college’s researchers. In fact, since the endowment of the Pitzer Center, Ohio State now boasts a top 10 national ranking in NIH grant funding among colleges of nursing at public institutions.

The Pitzer family’s Time and Change campaign investment was an anchor gift for the College of Nursing—an act of generosity that is already changing the lives of mothers and children through the groundbreaking work of Ohio State nurse scientists like Dr. Shannon Gillespie and Dr. Jodi Ford.

The Pitzer Center’s focus on mothers and children isn’t arbitrary. The United States ranks 54th in the world for infant mortality, and Ohio is in the bottom 25 percent of all states. Ohio’s maternal mortality rate is also higher than the national average. And those mortality rates are even worse for Black moms and babies.

“We've got a maternal-infant mortality crisis. It’s not a statistic in Ohio we’re proud of,” says Dr. Karen Rose, PhD, RN, FGSA, FAAN, Dean of the College of Nursing. “It affects the opportunities people have to live full, resilient lives. It affects everything. Maternal-infant mortality is a marker for overall population health.”

Babies born before 37 weeks have a higher risk of death and disability. In fact, across the world, preterm birth is the leading cause of death for children under 5 years old. The Pitzer Center’s Dr. Shannon Gillespie, PhD, RN, FAAN, wants to change that.

In the middle of Gillespie’s undergraduate years, her mom was diagnosed with an advanced cancer that eventually took her life. During that five-year battle, as Gillespie looked after her mother in Columbus, she couldn’t help but notice all the nurses who cared so well for her mom.

“The nurses stood out to me as these people who are absolutely making a difference in the world,” Gillespie says. “People get into nursing for different reasons, but a lot of times they just recognize illness and suffering and they want to do something about it. I always wanted to help people.”

While getting her master’s and PhD in nursing at Ohio State and joining the College of Nursing faculty in 2017, Gillespie began studying preterm birth, and she was struck by the reliance on history and symptoms when trying to predict it. “The biggest indicator of preterm birth right now is having a history of it,” Gillespie says. “But we don't want something to have to go wrong first.”

The goal, then, was to save lives by predicting and preventing preterm birth. To do that, Gillespie took an unconventional approach, drawing on multiple disciplines, including her undergraduate training in psychology. “A lot of the health effects we were studying were related to the immune system, which is super susceptible to stress,” she says. “Why is it that people who have a lot of chronic stress are more likely to have a preterm birth? Why are people in a natural disaster more likely to go into labor? We would see it over and over, but we didn't really know why it was happening.”

As a translational scientist, Gillespie addressed those questions by bringing together the worlds of psychology, biology, immunology and nursing. Through NIH-funded studies, she looked at key risk factors for preterm birth: stress, poor sleep, depression and anxiety, all of which can change how the immune system functions. And it turns out those changes can be measured with a simple blood test.

This groundbreaking new blood test, which has garnered national headlines, is the first of its kind to potentially predict the risk for preterm birth in early pregnancy. “That study was interrupted midway through by a pandemic. And it's an immune-related study, so I'm still analyzing the post-pandemic effects. But so far, we can predict risk with about 97.5% accuracy,” Gillespie says. “Now we have two questions in a post-pandemic world: Does this hold, and does it work for everybody?”

Gillespie is also working to prevent maternal mortality. “When we talk about pregnancy-related mortality, people usually think about delivery. But most pregnancy-related deaths actually happen after mom goes home from the hospital,” Gillespie says. “A lot of the reasons are related to cardiometabolic health. Mental health is really important, too. It’s a historically neglected period of time, but we're close to understanding this on a lot of fronts.”

For the MOMI Study, Gillespie partnered with Dr. Seuli Brill at the Ohio State College of Medicine and the Department of Internal Medicine at the Wexner Medical Center to test two different models of primary care during the year after childbirth. The study compares outcomes from traditional postpartum primary care with a model that takes care of mom and baby together in the primary care setting.

The Pitzer Center is uniquely suited for such collaborations. “I’m kind of like the interpreter in the middle of an epidemiologist and a clinician and a scientist. I sit right in between those things,” Gillespie says. “We’re not just bringing different disciplines together. We’re thinking about things from each disciplinary perspective. It’s a holistic approach to health care, which is what nursing is fundamentally.”

Traditionally, health care professionals have used samples of patients’ blood and saliva to investigate markers of health. But the Pitzer Center’s Dr. Jodi Ford, PhD, RN, FAAN, is trailblazing a new approach. She focuses on hair samples, measuring stress levels using cortisol in the hair.

Blood and saliva are great at measuring acute stressors in the moment, but since hair grows about a centimeter a month, it’s well suited for studying long-term, chronic stress. Three centimeters of hair can provide three months of accumulated cortisol, a primary stress hormone.

Research from Ford and others has linked adverse conditions like poverty and exposure to violence with irregular patterns of cortisol and high levels of inflammation, which could contribute to depression, death by suicide and substance use to cope with the psychological distress. The stakes could not be higher.

Ford’s Stress Science Lab is one of the most experienced in the nation, processing hair cortisol from researchers at Ohio State and across the country. Ford and her colleagues also train other scientists looking to start their own cortisol research programs. “It helps build the science around hair cortisol, because it’s relatively new,” Ford says.

Ford is leveraging the strength of her research program to help Columbus-area youth. Thanks to an NIH grant, she is in the second year of a five-year study looking at youth homelessness. The interdisciplinary project is a partnership with Natasha Slesnick, PhD, distinguished professor and associate dean for research at Ohio State’s College of Education and Human Ecology and founder of Star House. (The research team also includes Department of Sociology professor Christopher Browning and research scientist Beth Boettner, both in the College of Arts and Sciences.)

Star House is central Ohio’s only drop-in center open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. The nonprofit, which Slesnick founded in 2006, offers vital services for young people experiencing homelessness, including links to housing, education and health care, as well as access to counseling, food, clothing, hygiene items, laundry facilities and showers. For some youth, Star House is their only safe place. “They’re out on the street alone,” Ford says. “Many are youth who aged out of the foster care system and have no place to go.”

The study is a randomized controlled trial testing multiple evidence-based interventions for 300 young people ages 14 to 24, with follow-ups at three months, six months, one year, 18 months and two years. Star House therapists and case managers implement the interventions in hopes of discovering what is most effective (and cost-effective) for preventing opioid use disorder and improving mental health outcomes. Hair and blood samples help Ford understand how hormones and the immune system react to the good and the bad.

“We look at their social networks and where they go—safe places, and how those might change over time. And we also look at their mental health and stress,” Ford says. One of the interventions involves an advocate who provides social support and helps connect the young people to services. “Many of the youth qualitatively state how they've never had anybody care for them like that,” Ford says. “That connection—having an attachment to somebody—is very powerful.”

Ford can tie this work directly back to the Pitzer family. Not only has her research program received “incredibly helpful” financial support, but Ford also takes inspiration from the enduring impact of the center’s namesake. “We’re carrying on Martha’s legacy in helping to care for children and young people,” Ford says.

There’s a Wellness Walk at Ohio State’s College of Nursing that guides participants on a ¼-mile tour of Heminger and Newton halls, with inspirational quotes at various points along the way. One stop features a quote from Florence Nightingale: “Let us never consider ourselves finished nurses. We must be learning all of our lives.”

Martha Pitzer’s son David is proud to see that commitment to ongoing education at the Pitzer Center, just as he witnessed his mother’s commitment to lifelong learning. “Instead of trying to impose what she thought, she really enjoyed understanding how other people approach something,” David Pitzer says. “It goes back to research: All of us can do more than one of us.”

Throughout her life, Martha collected artwork of mothers and babies. Some of those pieces now hang on the walls of the Pitzer Center and in lactation spaces across Ohio State’s campus, continuing Martha’s legacy of warmth and care. The center also hosts the Martha S. Pitzer Lecture every fall, and her family continues to remain involved at the college. “We want the Pitzer Center to prosper. That means that we need to be available to assist,” David Pitzer says. “It’s an ongoing relationship.”

Joy Pitzer, David’s daughter, is also following in her grandmother’s footsteps, helping others as she finishes her master’s degree in social work at Ohio State. “I’m comforted by the fact that my grandma’s memory remains alive at the College of Nursing,” Joy says. “I think about her every time I walk by Heminger Hall.”

Just as Martha cared for others by projecting a sense of peace and calm, Heminger Hall provides that for students, faculty and staff. “I feel it every day I come in. It’s a calming space, and that was by design. We've tried to stay true to what we know is a healing place for people,” says Dean Karen Rose, who emphasizes caring for the caregivers. “You have to put the oxygen mask on yourself before you can put it on someone else. We want to be sure our graduates leave here feeling competent, confident and resilient. And we hope that notion carries over into patient care, to help preserve a calming environment.”

Whether the Pitzer Center’s nurse scientists are teaching students, caring for patients or working in the lab, they are answering their calling to care holistically. Collaboration is key. “If you're siloing, you're missing innovation,” Dean Rose says. “We can’t take care of patients without being part of a health care team. That’s what it looks like at the bedside, and that's what it looks like in research, too.”